The Rise and Fall of Alaska’s ‘Reindeer King’

Carl J. Lomen used legal loopholes and Santa Claus to build his meat business.

“Man will go anywhere for treasure.”

So Gudbrand “G.J.” Lomen told his 19-year-old son Carl in the summer of 1900, as the two caught their first glimpse of Alaska Territory from the deck of the S.S. Garonne. The flat, treeless expanse in front of them was punctuated by snow-capped mountains, tent-packed mining camps, and rusted heavy machinery. The sounds of ship whistles and jangling dogsleds pierced the icy air. The scene was worlds away from G.J. Lomen’s law practice in St. Paul, Minnesota, where the younger Lomen had previously worked for his father, a successful attorney and first-generation Norwegian-American immigrant.

Like countless voyagers of the era, the two had been lured northwest by tales of the treasures unearthed during the Nome Gold Rush. They never hit the mother lode that summer, but they stayed on as prospectors and entrepreneurs, eventually sending for the remaining Lomen clan to join them.

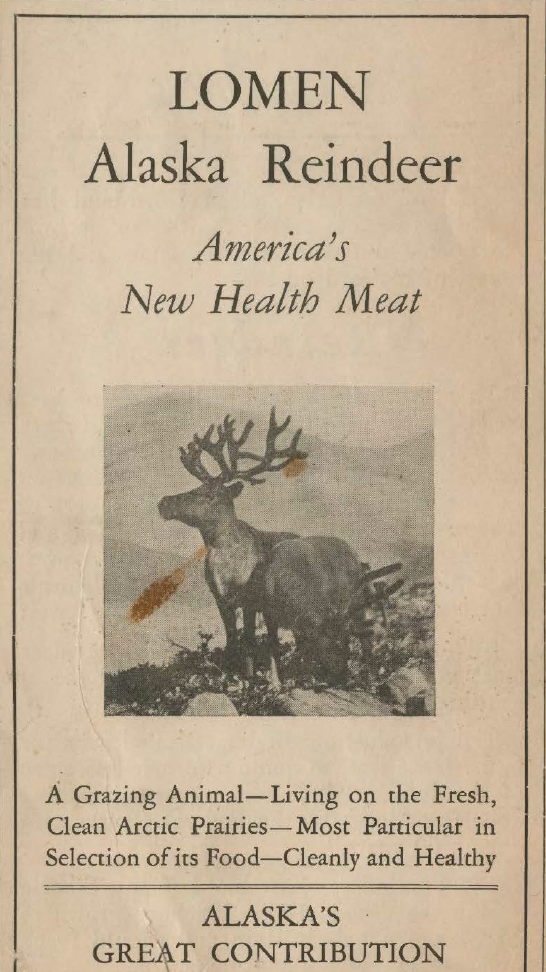

As the decades went by, Carl J. Lomen’s fate lay not in settling miners’ legal disputes, but in selling the other red meat: reindeer. He spent the bulk of his career coaxing dubious Americans to consider western Alaska’s swelling herds as an alternative to beef. This bombastic crusade earned him the nickname of the “Reindeer King.”

Reindeer aren’t native to Alaska, let alone North America. Their presence can be chalked up to Reverend Sheldon Jackson, the Presbyterian missionary and political figure who first arrived as the Territory’s general agent for education in the late 19th century. Claiming that earlier waves of white explorers and hunters had over-hunted animals like the whale and caribou, Jackson insisted that indigenous populations in the region would starve if not provided with a new food source. Just across the Bering Strait in nearby Siberia, the Chukchi people of Russia—who herded reindeer—provided Jackson with an idea.

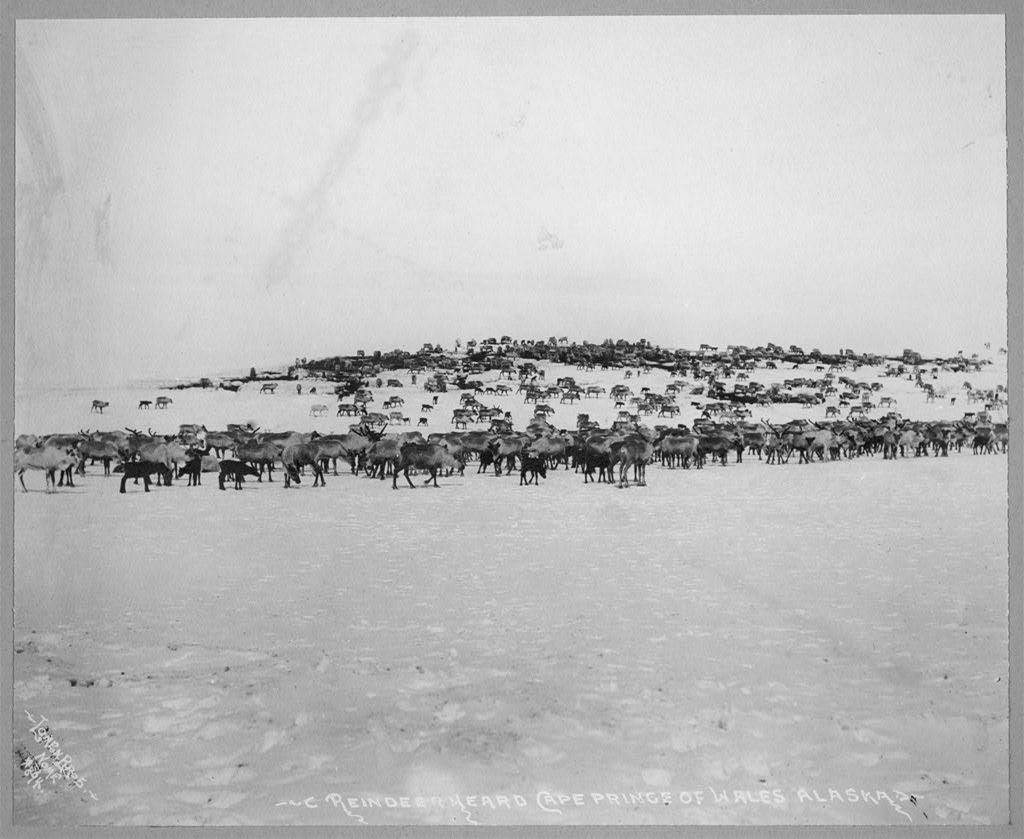

Genetically similar to North America’s wild caribou, the domesticated Siberian reindeer could theoretically thrive in Alaskan’s northern climes while providing meat, hides, milk, and transportation. Jackson also wanted to force Alaska Natives away from their traditional hunting practices, claiming that reindeer herding could provide a “civilizing” influence.

It’s dubious that the indigenous peoples of Alaska Territory were actually starving, notes Dr. Roxanne Willis, a writer and historian who researched the Lomens as a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University. Most likely, Jackson had observed cyclical food shortages, which were par the course for the Alaskan environment, plus there were regional trade networks to fall back on. Still, the reverend’s claims resonated with enough Americans that Jackson was able to raise money—first via donations, and later from Congress—to fund multiple reindeer-procuring trips to Siberia.

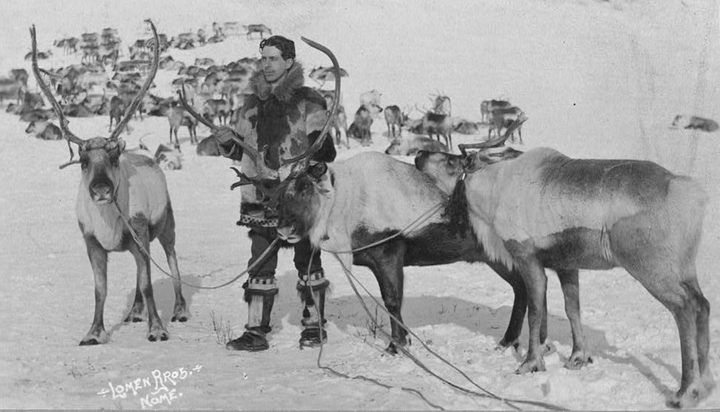

Jackson brought hundreds of reindeer back to the Seward Peninsula along with several Chukchi herders. Due to cultural clashes with the Chukchis, Jackson would soon replace them with Sámi reindeer herders from northern Norway while also transporting fresh heads of Nordic deer. As these mixed herds multiplied, Jackson’s original scheme grew in scope. He believed that reindeer herding could transform the remote American territory into an economic powerhouse run by the state’s Native inhabitants.

Lomen also believed that reindeer were Alaska’s future. But unlike Jackson, his quest was driven by personal ambition.

Lomen’s father had enjoyed success in Minnesota, but his career reached new heights in Alaska Territory, where he eventually became a federal judge. He expected similar greatness from his children: “I know [Carl Lomen] had a lot of pressure from his father to be as entrepreneurial and successful as he had been,” Willis says. Whether or not driven by familial pressure, the onetime lawyer-in-training developed a reputation in Alaska over the years as an opportunist with few scruples and questionably acquired assets.

Lomen would always remember his first encounter with Alaskan reindeer shortly after arriving in Alaska Territory. “I was prospecting for gold along the beach some 30 miles west of Nome,” he recounted in his 1954 autobiography, Fifty Years in Alaska. “I’d just had a sparse lunch and was going up the beach when, to my astonishment, I saw ahead of me a herd of several hundred reindeer. I was scared and stopped dead in my tracks … I had no knowledge of reindeer habits and wondered if these strange animals would suddenly attack me.” While soon assuaged by a herder’s appearance, Lomen’s “curiosity had been permanently aroused,” he wrote. He’d found a new source of gold to tap.

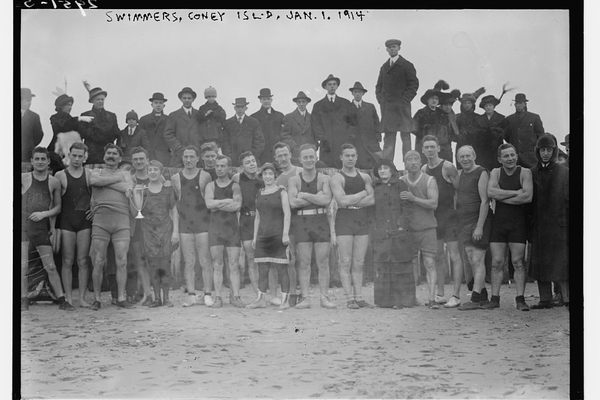

Only Alaskan Natives could lawfully own and sell female reindeer. But years later, in 1914, a loophole presented itself to Lomen: Sámi herders, too, were allowed limited reindeer ownership as part of their teaching contracts with the U.S. government, and they technically could sell the animals to anyone once said contracts expired. Conveniently, Lomen knew of such a person looking to offload his herd of 1,200, and they struck a deal.

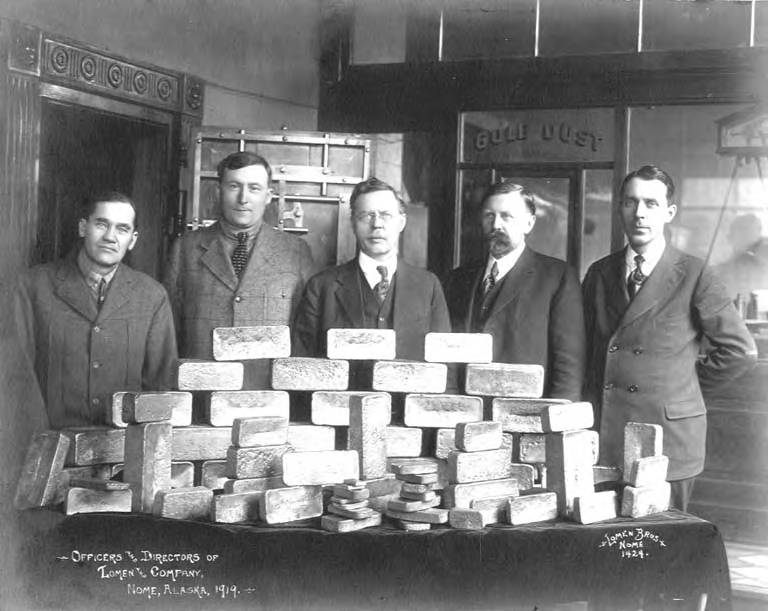

At that point, the Lomen family had settled into new roles in Nome, with G.J. Lomen’s five sons owning a local newspaper, a photography studio, a drug store, and other local businesses amongst themselves. They consolidated their money-making initiatives under the umbrella name “Lomen & Company.” With help from investors, the Lomen Reindeer Company was born.

By the 1920s, the Lomens had successfully skirted (or outright ignored) enough technicalities to become prosperous reindeer entrepreneurs. They recognized the hide’s utility, researching whether soldiers and pilots could wear waterproof skin suits and using it to sew sleeping bags and other gear for polar explorers. But their main interest was meat: freezing it, transporting it, distributing it, and selling it. Under Carl Lomen, with his brother Alfred Lomen serving as his right-hand man, the company controlled nearly every aspect of its production chain, from building slaughterhouses and deep-freezing facilities to organizing transportation and shipping.

Working beneath the two brothers were many Sámi herders and Alaskan Natives, who, according to Bates College anthropology chair Dr. Jennifer Hamilton, “very quickly went from herders to laborers”—a far cry from the government’s original plan for the latter to become self-sufficient reindeer stewards, and even further from their traditions as hunters.“The Alaskan Native peoples, especially in the Seward Peninsula, were alienated from the land and made into reindeer herders,” Hamilton says. “Then that was taken over.”

Carl Lomen claimed that Alaskan herders’ interests wouldn’t be threatened since they sold their reindeer products within the state and his went out of state. Assumptions like these—along with other major flaws in his master plan—would lead to the Lomen Reindeer Company’s undoing.

Lomen may have named his autobiography Fifty Years in Alaska, but much of his career was spent in New York City and Washington D.C., currying favor with investors and politicians in an endless quest to peddle reindeer meat to the masses. “He was one of these larger-than-life characters who believed that if you build it, they will come,” Willis says.

Lomen gained friends in high places, marrying Laura Volstead, the daughter of Minnesota congressman and Prohibition figurehead Andrew Volstead, in 1928. A tireless promoter and networker, he served reindeer meat at dinner parties for elite clubs, extolled reindeer’s commercial potential on the lecture circuit (his wife provided the meat-cooking demonstrations), and convinced officials to organize “Reindeer Weeks,” complete with fresh reindeer steaks available at local grocery stores.

“It is similar to a medium lamb or a mallard duck, a domestic, not a game meat,” he told one audience in New York. He persuaded high-end restaurants to place reindeer meat on their menus and arranged for trains to serve reindeer meat in dining cars. Even dogs got a taste, when Lomen pitched the idea of reindeer meat to pet food manufacturers.

But Lomen’s most over-the-top marketing scheme, which began in 1926, involved department store chains such as Macy’s. That Christmas, he sent reindeer to various retail locations, where the animals would parade before delighted crowds as “Santa’s reindeer” led by Alaskan Native or Sámi reindeer herders. These displays helped solidify “Santa and his reindeer” as a cultural touchstone, forever reinforcing the image of Old St. Nick as a jolly man in a red suit behind a sleigh.

Lomen was seemingly unstoppable. By 1929, Americans had purchased nearly 6.5 million pounds of reindeer products, mostly as meat from the Lomens. Then, the stock market crashed. As the global economy fell apart, so did the Lomens’ reindeer business.

Long-brewing tensions between Alaskan herders—who had never succeeded in selling reindeer meat in-state—and the Lomens came to a head. Competitors waged a fierce lobbying campaign against them to boot: “The beef industry was very opposed” to the Lomens’ dealings, says Nathan Muus, co-editor of BÁIKI: The International Sámi Journal. “They obviously saw the parades in U.S. cities, and they were very alarmed. They did not want reindeer to end up in restaurants and supermarkets.”

And despite Lomen’s long-standing dream of Alaska developing a national reindeer market—one that could potentially rival Texas’s cattle industry—the whole operation just wasn’t scalable. Operating costs were high, plus there were too many reindeer in Alaska and not enough herders. Then there was the meat itself. “Most of the food critics were like, ‘This was the worst thing I’ve ever tasted,’” Willis says.

That year, in 1929, federal officials launched an investigation into Lomen Reindeer Company’s dealings and their herding issues in Alaska. Charges levied by Native Alaskans against the business were damning, ranging from monopoly abuse to outright reindeer theft. At first, the investigation favored the Lomens. But following several years of squabbling, inquiries, and hearings, “the government ended up buying out Lomen Reindeer Company for about $500,000 in the mid-1930s,” Willis says.

It was a huge come-down for Lomen, whose holdings were once assessed in the millions. In 1937, Congress passed the Reindeer Industry Act, which for decades afterwards formally limited reindeer ownership in Alaska to Native Alaskans only. The government then redistributed all the purchased animals—including Lomen’s.

Overlooked amidst all this were the Sámi people who came to Alaska from northern Norway. Many who remained in Alaska following the expiration of government teaching contracts had owned their own herds for generations. But under new rules, these Nordic-born reindeer herders—newly classified as “white” in America—were no longer allowed to keep them, unless they had become part of an Alaskan Native family. “They ended up having to give up their reindeer herds as well, and they had been recruited as the experts,” Willis says. (A current art exhibition at Seattle’s National Nordic Museum, titled Mygration, traces the Sámi often-overlooked role in teaching reindeer husbandry in North America.)

By the decade’s end, “Reindeer King” Carl Lomen had officially lost his crown, his reindeer—and a large bulk of his livelihood. He had also spectacularly failed at making reindeer the new beef. “He had a vision, and he built the infrastructure for it prior to realizing if he had a market—and prior to really thinking about what was legal,” Willis says. Still, in spite of his checkered legacy, he’ll be forever connected with reindeer in North America—and, due to his Macys’ spectacles, with Christmas.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook