Found: The Oldest-Known Photograph of Enslaved African Americans With Cotton

The daguerreotype records their faces, but not their names.

The image is simple and haunting. Ten enslaved African-American people stand in front of a two-story, white clapboard building, some with baskets of cotton on top of their heads. A boy bows his head in the lower-left corner, his back to the camera. It’s a quarter-plate daguerreotype, a little larger than a deck of cards but brimming with details visible only when magnified: the individual leaves of the plants encircling a well, the woven wicker of the baskets. The antebellum photograph, believed to date back to the 1850s, is the oldest-known image of enslaved people with cotton, the commodity that they were forced to harvest.

Recently, at Cowan’s American History auction, the Hall Family Foundation purchased the photograph for $324,500, on behalf of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. “I had never seen an image like this before,” says Jane Aspinwall, the curator of photography at the Nelson-Atkins Museum.

Images of enslaved African-American people are relatively rare, and were almost always taken at the behest of the slaveholder, according to critic Stephen Best in “Neither Lost nor Found: Slavery and the Visual Archive,” published in a 2011 issue of the journal Representations. “However exhaustive one’s catalog of the visual archive of slavery, it will always be lacking in works by slaves themselves,” he writes.

Most of these photos were taken on elite, coastal plantations that would have enslaved hundreds of people. But this daguerreotype sheds light on how pervasive slavery was, even among what might have been considered the Southern middle class, according to a story in Fine Books & Collections Magazine.

The image is likely set on a rural plantation owned by Samuel T. Gentry in Greene County, Georgia, according to the auction listing. Gentry enslaved between 15 and 18 people in Georgia from 1850 to 1860, according to “slave schedules” that were part of the federal census. Aspinwall believes Gentry would have staged the image to display his wealth. “It’s almost like a property record,” she says. Cowan’s Auctions acquired the daguerreotype from an estate sale in Austin, Texas, of belongings from one of Gentry’s descendants. According to the auction listing*, the man in the left corner of the image is believed to be Gentry himself, leaning on a cane and possibly restraining a leashed dog. The photographer is unknown.

Beyond its subject matter, the photo is unusual in another way. “A majority of 19th-century daguerreotypes were taken indoors,” Aspinwall says. “Anything as rare as this was super special.” In 2016, Cornell University Library digitized a lantern slide image of African-American people picking cotton outdoors, titled “On the Suwanee River.” The slide dates to the late 19th-century, a few decades after the Gentry daguerreotype was taken, and likely after the end of slavery. Aspinwall also sees the photos’ “slice of life” composition as unusual for the time.

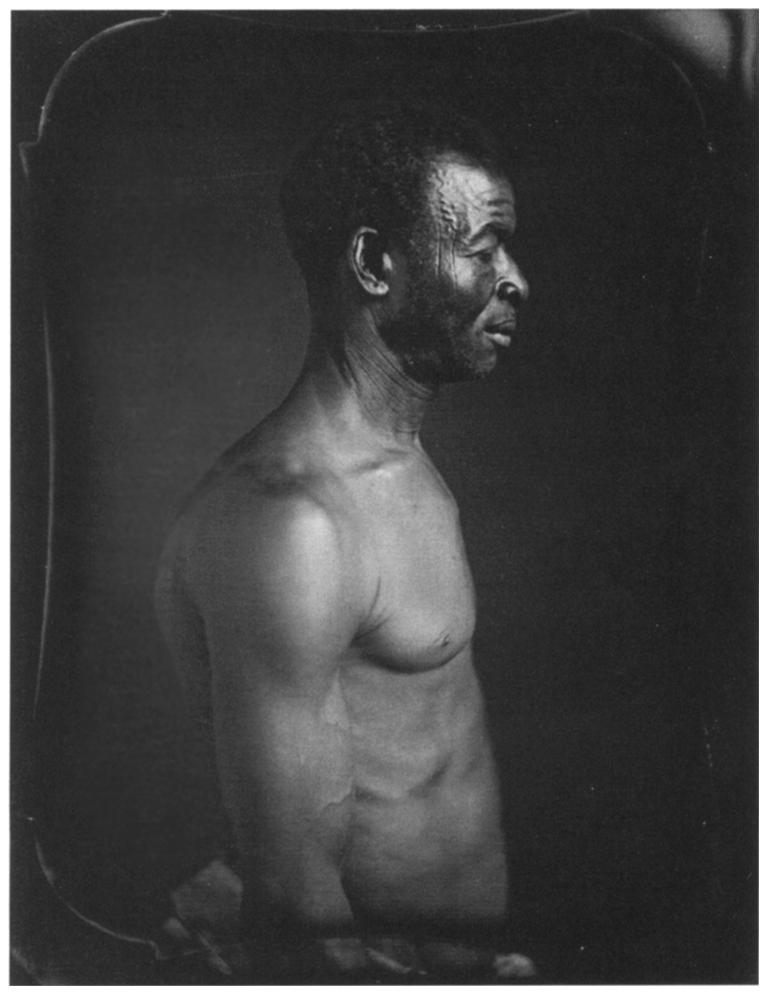

Some of the most infamous daguerreotypes of enslaved African Americans were commissioned by Louis Agassiz, a Swiss-born biologist whose name still appears on many buildings at Harvard University. Agassiz believed in the discredited idea of polygenism, which claimed that different human races originated separately, and which is now considered a type of scientific racism. He had 15 images made of seven enslaved people to prove this theory, researcher Suzanne Schneider writes in a chapter of Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity. The daguerreotypes are currently held by Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. In 2019, Tamara Lanier, a descendent of Renty and Delia, an enslaved father and daughter photographed in the series, argued in a lawsuit that the daguerreotypes rightly belong to her family.

Though the Gentry daguerreotype is not yet up for display at the Nelson-Atkins Museum, Aspinwall says her team has discussed including it in a future, small-scale show featuring images related to abolition. The museum’s collection contains several daguerreotypes of known abolitionists, such as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Beecher Stowe, as well as daguerreotypes taken by African-American photographers. “These big names worked against this whole notion of slavery, and this new image helps complete that conversation,” she says.

The names of the enslaved people immortalized in the daguerreotype, however, are likely lost, recorded only as numbers alongside the Gentry name. This kind of erasure is an unfortunate part of most archives of slavery. In his paper, Best writes that one image, said to depict two enslaved boys, was challenged by skeptics who still dispute its origins and contents. Of the skeptics, he writes: “If they achieved anything it was to show how thoroughly, in the archive of slavery, to be found is to remain undiscovered.”

* Correction: An earlier version of this story stated that the man at the left of the photograph was white. His race is not known. This story was updated to attribute that interpretation to the auction listing.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook