Why is Everyone Fighting Over the Skull of ‘Brigand Villella’?

The answer involves pseudoscience, politics, and a burglary at a windmill.

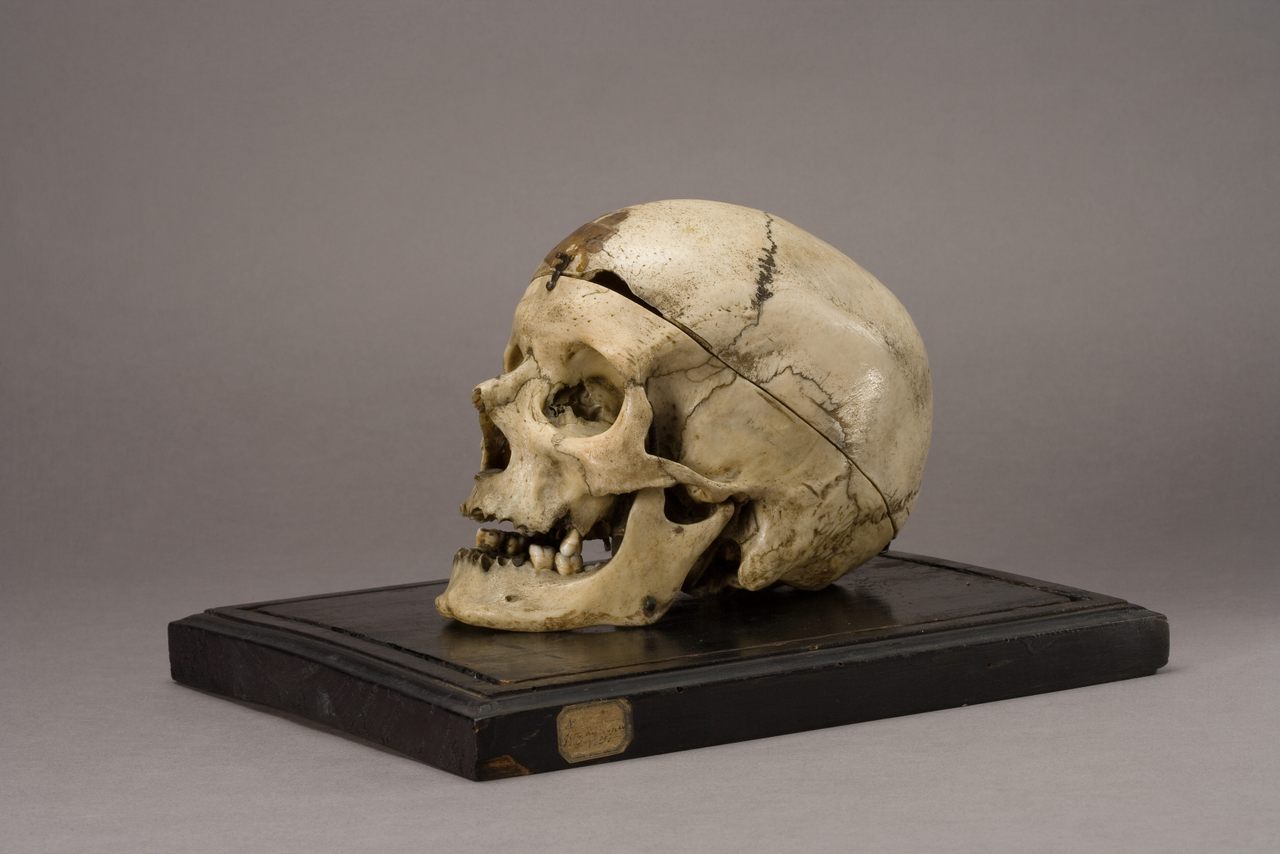

“On a dark, cold morning of December 1870, while analyzing brigand Villella’s skull, I had a sudden realization … and solved the problem of the delinquency’s nature.” With these words, Cesare Lombroso, a prominent Italian scientist from the late 19th century, described the moment many consider the symbolic beginning of criminal anthropology: the discovery of a physical trait in the human skull which Lombroso held accountable for all deviant behavior.

The scientist is now long dead and his theories have been discredited, but the skull of this mysterious, controversial brigand—or outlaw—survives and is currently at a center of a passionate dispute between those who want to give Giuseppe Villella a proper burial and those who believe that the importance of this remain transcends its biological dimension and want to continue to display it as a cultural asset.

Born in 1835, Cesare Lombroso lived in an age in which established religious truths were being challenged and replaced. He believed that the scientific method would offer a solution to all human queries. The scientist was particularly concerned with the problem of criminality; crime was ravaging the recently formed Italian nation and threatening its stability. Inspired by the evolutionary theories of Darwin, Lombroso was convinced that there was a genetic predisposition to savagery and that he would be able to identify criminal individuals by using physiognomy—a pseudoscience that held that the shape of the human head was an indicator of the individual’s personality.

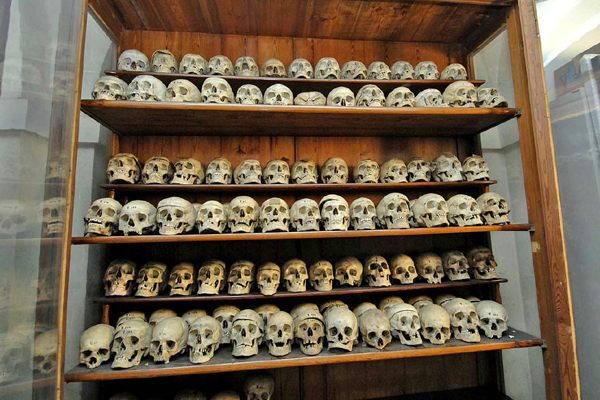

After analyzing and measuring hundreds of skulls, Lombroso finally found a “median occipital dimple” in brigand Villella’s skull, an indentation which resembled the one found in lemurs and rodents. This was for him the proof that criminal behavior had a biological nature. “Born criminals” were in fact “genetic throwbacks,” displaying atavic, remote characteristics in the evolutionary scale which were responsible for their deviant personality, Lombroso believed, and it would be possible to recognize such individuals by the existence of some physical stigmata.

Lombroso based his entire life’s work on this theory, which generated passionate debates within the international scientific community and fascinated the wider public. By the 1880s, his theories had reached the pinnacle of their fame, and the press celebrated the distinguished “creator of the anthropological science” as a “well known, honoured and esteemed person by every men of science in each corner of the world.”

Throughout his life, Lombroso treasured the object that was the cornerstone of his work; Villella’s skull sat on his desk until the scientist’s death in 1909. His heirs then kept the skull until 1946, when they decided to donate the furnishings of the scientist’s private studio to the museum which already held most of the human remains that had been a part of Lombroso’s collection. The skull went on display for the first time in 1985, when two books and a documentary about Lombroso generated an unexpected renewed interest in the scientist. And when a new Lombroso museum, the Museo di Antropologia criminale “Cesare Lombroso,” was inaugurated in Turin in 2009 to celebrate the centenary of the scientist’s death, an entire room was dedicated to Villella’s skull. It was displayed in a glass showcase and contextualized with an informative video about the scientist’s discovery and his fallacious conclusions, underlining the skull’s importance in the history of scientific mistakes.

The opening of the museum dedicated to the 19th-century scientist caused an immediate, unexpected uproar. Southern Italian parties and movements mobilized and denounced the museum as “obscene, inhuman, racist… the denial of God;” the institution was depicted as a “mass grave” of Southern patriots and Lombroso as responsible for the “annihilation of dozens of thousands of Southerners.” Villella was depicted as someone who “proudly took part of the resistance movement against the annexation, pillage and destruction of the South,” and the No Lombroso Committee was formed to demand the return of Villella’s skull to Motta Santa Lucia, the town in which he was born.

Maria Teresa Milicia, an anthropologist from Padova University, was puzzled by the enormous controversy. She decided to try to reconstruct brigand Villella biography. “I was surprised to realize that no one ever heard about this ‘local hero’ in the town in which he was born,” she says. After a year spent digging through the town’s dusty, unorganized local files, she determined that Giuseppe Villella had been a minor thief who was condemned in 1844 for stealing a few items in a windmill.

“This discovery was quite astonishing, because this profile fit neither Lombroso’s description that painted Villella as a taciturn criminal, nor the committee’s one of a heroic patriotic figure fighting against Italian unification,” Milicia says. Both had used the skull to further their own political agendas: Lombroso tried to make Villella into an outcast with a criminal lifestyle in order to prove his theories, and the committee painted Villella as a meaningful local hero in order to legitimize the restitution request and secure a place in the regional political scene.

In fact, “many Western museums have had to deal with the return of human remains contained in their collections,” says Silvano Montaldo, the current director of the Lombroso museum, “but in Italy this problem is characterized by distinctive political features.” In most cases, the restitution requests are made by Indigenous groups who wish to give a proper burial to their ancestors—but Montaldo and other scholars are convinced that in this case the requisition is not motivated by truly humanitarian ideals but political ambition

160 years ago, the Italian territory was a mosaic divided between several foreign powers, such as the Bourbonic Spanish who ruled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in the South. In recent years neo-Bourbonic groups have formed and grown in popularity by exploiting the resentment of Southern Italians who feel neglected and disrespected in their country, Montaldo explains. In many cases, these groups have distorted historical data to rewrite history. In the neo-Bourbonic telling, “the Bourbons are celebrated as benefactors and all the brigands as patriots who defended the South from the bloody Northern conquest, which caused a true genocide of Southern populations,” he says. “Lombroso is often depicted as a theoricist of such genocide, but this is a totally anti-historical thesis.”

In 2012, the No Lombroso Committee’s arguments triumphed, and a court ordered the restitution of the remains of their “glorious hero,” but the Lombroso museum won two court appeals in 2017 and 2019 which legitimized the status of Villella’s skull as a cultural asset. The No Lombroso Committee still pledges on its website that it won’t stop “until every single human remain still present in the museum finds a worthy Christian grave,” and the “horror museum” continues to be depicted by the committee as the place “where the remains of glorious Southern soldiers, decapitated for the studies of Lombroso, are still exposed as trophies.” Recently, an Italian senator put forward a parliamentary motion asking for the closure of the museum, comparing it to a “hypothetical Dr. Mengele’s museum in Germany.”

Montaldo denies every persistent accusation against the museum: “This is not an apologetic museum intended to celebrate Lombroso…, but an university one which offers a balanced and contextualized information about the historical collection retrieved by Lombroso during his research activity, without hiding the racist contours of his ideas, which were fairly common in the anthropology practiced at the time.”

“The real history is actually much more fascinating than the fiction,” Milicia says. “Giuseppe Villella was not a hero or a villain, but a victim of the brutality of his times”—times characterized by a violent civil war with a complex web of allegiances, rampant chaos and poverty, and utter neglect of the populations. Villella’s skull could today become an invitation to a complex reading of this sensitive part of Italian history, and to the limits of the scientific theories and paradigms that helped to shape the world in which we lived today.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook