Exploring the Mysterious Allure of Mazes and Labyrinths

On the joys and frustrations of losing yourself.

Excerpted from The Puzzler by A.J. Jacobs. Copyright © 2022 by A.J. Jacobs. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

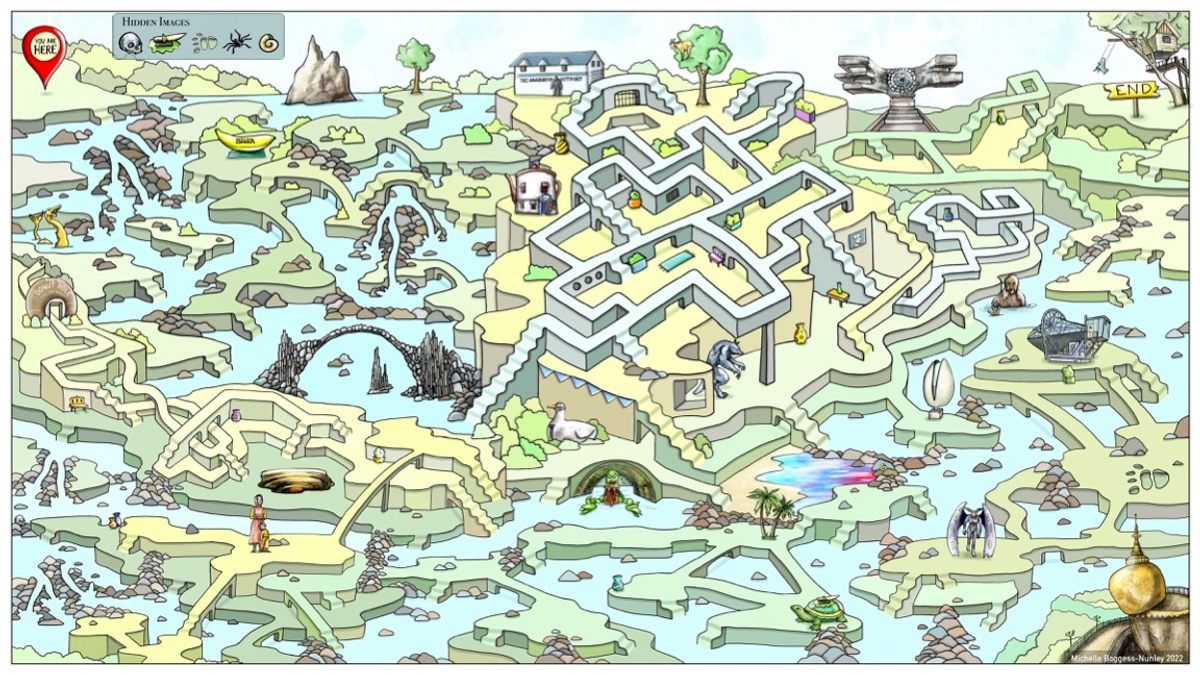

Want to try your hand at a challenging paper-and-pencil maze? Check out an original Atlas Obscura maze from world record-holding maze artist Michelle Boggess-Nunley!

On a fall weekend before the pandemic quarantine, I go to the Labyrinth Society Annual Gathering to learn about mazes. This turns out to be a big mistake. A wrong turn, appropriately enough.

I’m informed of my error soon after arriving at the retreat in rural Maryland. One of the conference organizers, a tall man from Tasmania, tells me in a gentle but stern tone that the gathering of the Labyrinth Society is NOT the place to study mazes.

Labyrinths? Yes. Mazes? No.

They are two very different things. And one is better than the other.

“God created the labyrinth to help people deal with the trauma of mazes,” he tells me, as we stand in a field near a stone labyrinth. He is not smiling.

I’d always thought of the two words as synonyms, but devoted labyrinth fans say they are oceans apart.

Mazes are puzzles. You have choices. Do I turn left? Right? Go straight? The point is to get lost before finding the exit.

Labyrinths, on the other hand, are not puzzles. Labyrinths offer zero choices. You follow a single winding path from start to finish. Their purpose isn’t to entertain, it’s to enlighten. According to labyrinth fans, walking a labyrinth can be a profound experience, a meditative and healing experience. Sometimes even a life-altering experience, akin to St. Paul’s road to Damascus or Steve Jobs’s acid trip.

Many of the hardcore labyrinth fans see mazes as a source of anxiety, confusion, and stress. “I don’t want to make any decisions,” one man told me during lunch break. “I make enough decisions in my real life. One path in, one path out, that’s what I like.”

Much to my surprise, I learn that labyrinths have had a considerable resurgence in the last few decades. The modern labyrinth craze was ignited by a 1996 book called Walking a Sacred Path by Lauren Artress, an Episcopal minister. She wrote about her experiences walking the labyrinth made of stones embedded in the floor of the Chartres Cathedral in France, describing it as a powerful way to pray.

Since then, labyrinths have been embraced by various spiritual seekers—Christians, Buddhist-influenced mindfulness fans, New Agers, and users of psychedelics. Thousands of labyrinths, both temporary and permanent, have popped up in private homes, hospitals, retirement communities, rehab centers, and church parking lots. Some are made of rocks artfully arranged in grass. Others are painted on pavement. Still others are printed on portable tarps. (Unlike mazes, labyrinths rarely have high walls; they are usually knee-high or lower.)

But all labyrinths share one trait: “The labyrinth is not a puzzle to solve,” a woman tells me. “The puzzle is you. And you solve it by walking the labyrinth.”

Since I’m writing a book on puzzles, what should I do? Maybe I should take the next train home and never speak of this again. Or maybe I need to relax and explore the idea of the anti-puzzle. The joys of freedom FROM choice. The novel idea of not subjecting myself voluntarily to confusion and hardship. And maybe work on that “puzzle of you” thing.

So I spend the day exploring labyrinths with about a hundred other gatherers from all over the world. I attend speeches about the history of labyrinths, from patterns drawn on pottery in ancient Syria, to medieval Swedish stone arrangements.

I listen to testimonials of people who talk about energy vortexes and chakras. (This New Age lingo is partly why some conservative Christians disapprove of labyrinths, seeing them as too pagan.) I read pamphlets about how labyrinths have supposedly cured people’s arthritis and nearsightedness and I hear about how labyrinths can enhance life’s rituals, including marriage (the couple walks in separately, and leaves together) and divorce (the opposite, of course).

And, of course, I walk a labyrinth.

The organizers have set up several on the hotel grounds, and the one I choose sits in the field behind the hotel. The labyrinth consists of dozens of square stones arranged in a spiral and embedded in the patchy brown-green grass. It’s about the size of a tennis court.

I’ve joined a dozen other walkers for a workshop being led by Mark Healy—the Tasmanian who warned me of mazes’ psychic toll. Mark is a young-looking blond man of 62 and father of seven. He’s wearing a black T-shirt that says, “I lost my mind in a labyrinth but gained my heart.”

In a speech the previous night, Mark had talked about how labyrinths saved his sanity. In 1999, he was the owner of an organic food business that went bankrupt. He spent six months building a labyrinth to help him through the ordeal. “It purged me of shame and grief,” he said.

This labyrinth has two entrances side-by-side.

“If you are feeling masculine energy,” Mark tells us, “then go right and come out left. If you are feeling feminine energy, go left and come out right.”

Hold on. I thought the whole point is I wouldn’t have to make choices! Regardless, I’m not feeling either gender’s energy particularly strongly. I decide to go with the male route.

I step onto the path and walk slowly, like I’m in a funeral procession. I’m hoping for a mind-blowing experience. A blast of trumpets, a technicolor hallucination of a world beyond. This is not happening. But I’m going to do my darndest to get the most that I can out of this labyrinth. I focus on the sound of the grass crunching under my sneakers, the breeze on my cheek, the brisk air filling the alveoli in my lungs, the slight dizziness when I do a 180-degree turn, which makes me wobble drunkenly and almost bump into another walker.

I focus on not focusing so much.

Three minutes later, I step out of the labyrinth. Mark is waiting at the end with a beatific smile and his hands in the “namaste” position.

“You lost your virginity!” Mark congratulates me.

I smile. I can’t say I am reborn. But I do feel my pulse has slowed. I’m relaxed, serene, like I’ve just had a nice glass of white wine. Which is not nothing.

It’s certainly a contrast to wrestling with a puzzle. And in some ways, a welcome one. I think of Barack Obama’s dream of opening a T-shirt shop. He once said he was so sick of hard decisions that he fantasized about opening a T-shirt shop on the beach that sold only one item: a plain white T-shirt, size medium. Freedom from choice. Several years ago, I wrote a book in which I followed all the rules of the Bible, and even though I’m not religious, I saw the appeal of a highly structured life. The freedom to choose has many benefits, but in certain circumstances, so do strict limitations. Should I work on the Sabbath? No. I don’t have to think about it or weigh the pros and cons. The answer is clear.

Puzzles follow a narrative: You struggle, you struggle some more, then you break through to the joy of the solution. It’s the same narrative we like in our books and movies. Conflict, then resolution. But sometimes I agree with Mark: Why should we have to endure that painful conflict phase if we don’t have to? Maybe we’re unhealthily masochistic. It’s why I have an odd habit that drives my wife crazy: Sometimes I watch the first half of a romantic comedy, then turn it off. I just want to see the part where the couple is falling in love and the montages of ice-cream eating and roller skating. But as soon as Act 2 starts, with those stressful misunderstandings and complications, I’m out.

Don’t get me wrong. I still love puzzles, even with the anxiety they provoke. Partly because of the anxiety. But I can see the appeal of the labyrinth.

Before I leave the Labyrinth Gathering, I buy a book in which each page contains a simple black-and-white labyrinth. You’re supposed to trace the labyrinths with your index finger and get that mental peace without leaving your sofa. Perhaps, when I’m banging my head against a frustrating puzzle, tracing these simple, choice-free paths will be a meditative gift.

The Michelangelo of Mazes

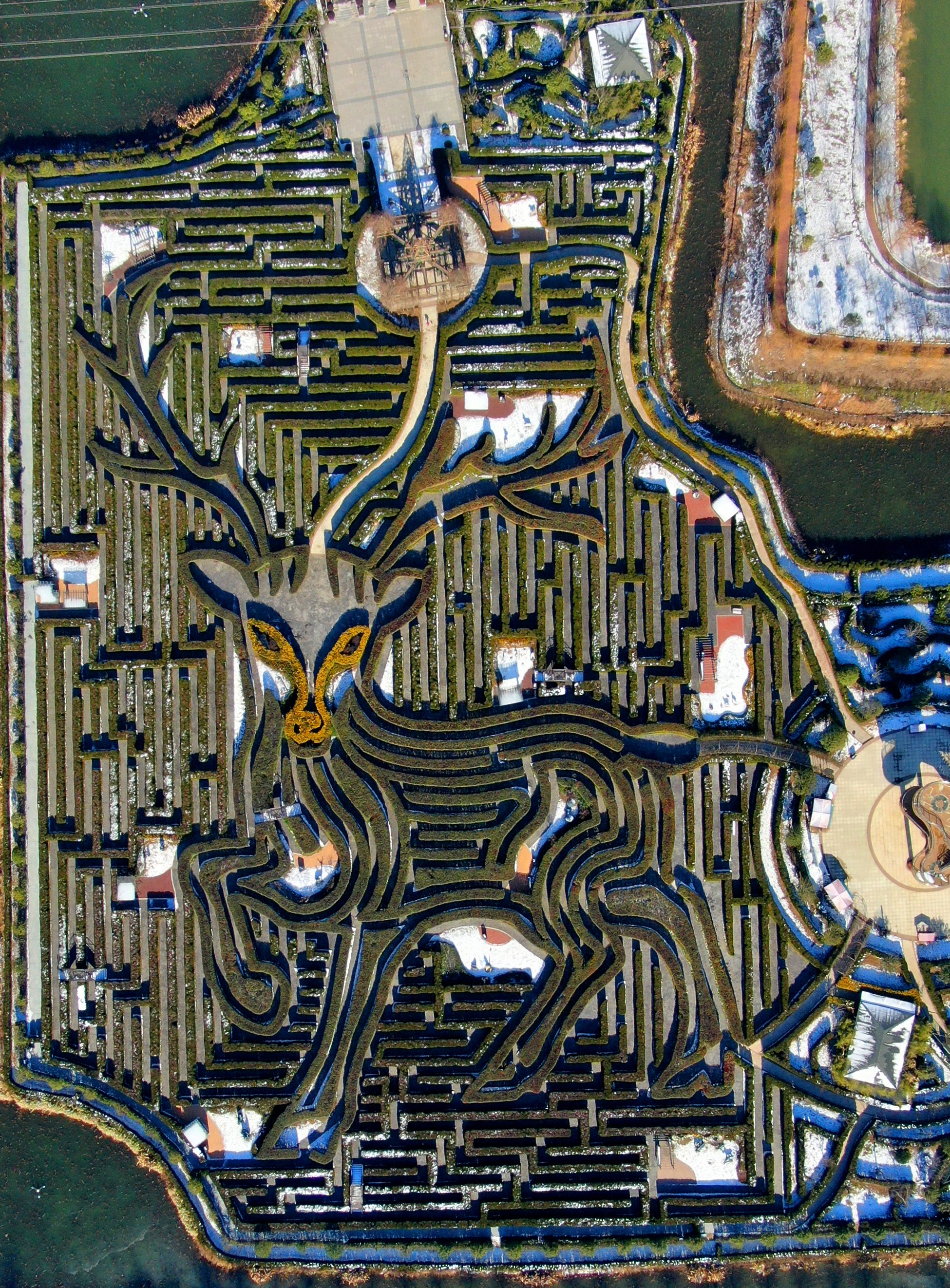

After so much maze skepticism, I wanted to hear a pro-maze perspective. So I set up a Zoom call with a British man named Adrian Fisher. Adrian is the most prolific maze designer “in the history of humankind,” as he puts it, modestly. He and his company have designed more than 700 mazes to date. He’s created mazes that can be found in 42 countries on six continents. He’s designed them for amusement parks, museums, and private homes. He’s made them out of hedges, mirrors, corn, colored bricks, and spraying water. He has set nine world records, including for the biggest permanent maze, called “The Maze of the Butterfly Lovers,” in China, with more than five miles of hedge-lined paths. (Another maze in China, this one in the shape of an elk, recently broke the Butterfly Maze’s record for largest maze.) The polar opposite of Mark Healy, Adrian is convinced that mazes are a great source of pleasure.

Sometimes very physical pleasure.

“I was in a corn maze in Southern England and there was a couple there with a baby,” Adrian tells me. “They came up to me and said, ‘Did you design this maze?’ I said yes. They said, ‘This little baby was conceived in this maze two years ago.’ ”

“Weren’t they afraid of getting caught?” I ask.

“I suppose that was the fun of it.”

Adrian is speaking to me from his home office in Dorset, England. He’s got bushy gray eyebrows, and he is wearing a navy blazer. His office is packed with piles of books on gardening and masonry.

Adrian’s conversational style is, appropriately enough, filled with unexpected byways and occasional dead ends. He talks about water skiing barefoot in Hong Kong and longbows in medieval warfare.

“As you may have detected,” he says, “my life consists of telling stories. Some of them are true.”

Eventually, we do discuss mazes, his first love.

“I’m an artist,” Adrian says. “And my chosen medium is mazes.”

How did he embark on this curious career path?

A puzzle fan since childhood, Adrian created a hedge maze in his father’s garden when he was 24. He decided it was his life’s calling. His first commissioned maze opened in 1981 at a historic British manor near Oxford.

Some of his more notable mazes? He helped design a Beatles-themed maze in Liverpool with a yellow submarine at its center. “The Queen opened that one,” he says.

There’s the maze at the passenger terminal at Singapore’s Changi Airport. “Doesn’t that cause people to miss flights?” I ask.

“Yes, I’ve read that has happened several times.” He doesn’t seem particularly guilt-stricken.

And the maze on the side of a 55-story skyscraper in Dubai. “It’s not to be attempted unless you happen to be Spider-Man,” Adrian says.

He’s incorporated rotating floors, walls that change colors, and waterfalls that part when you walk through them.

The beauty of a maze, says Adrian, is that when you solve it, “you walk out one inch taller.” It imbues a sense of danger, but not too much danger, followed by joyous accomplishment.

“When I’m designing a maze, it’s like I’m playing a chess game with you. But I have to make all my moves in advance. And I have to lose.”

He says mazes are best when they’re a social activity. “You have to share the decisions, figure out how to work together.”

He loves the symbolism of mazes. “Mazes can work on so many levels. They contrast the rigidity of man’s designs with the exuberance of nature—and the folly of man trying to control nature.” And he adores the mystery. “Mazes are like bikinis of life. They have to hide the important bits, but still reveal enough to keep things interesting,” he says. I suspect I’m not the first one he’s used that line on.

Mazes Start Here

Adrian is also a writer, and has authored no fewer than 15 books on mazes. Some are collections of his pencil mazes, a genre that was faddish in the 1970s and 80s. Others focus on the history of mazes. As I dug into Adrian’s history books, as well as those by other authors, they reinforced my contention that history is almost always far weirder than we imagine.

Consider the tale of the most famous maze of all time: the ancient Greek labyrinth, home to the fearsome Minotaur. (Just to complicate things, it’s usually called a labyrinth, but it might have been a maze, since people got lost in it.)

I knew the bare bones of the Minotaur myth but not the full story. And the full story isn’t just weird. It’s depraved. As in Human Centipede–level depraved. It reinforces my belief that ancient societies were far more disturbing than the sanitized versions we are taught.

With that warning, here goes:

The Greek god Poseidon got angry at King Minos of Crete for failing to sacrifice a white bull to him. So Poseidon, using flawless misogynistic logic, decided to punish King Minos’s wife. He put a curse on the queen that made her fall madly in love with the white bull.

The queen tried to seduce the bull, but the bull wasn’t interested. Not his species. Desperate, the queen hired Daedalus, Greece’s greatest inventor, to help with her cause. Daedalus’s task: build a realistic-looking cow out of wood and cowhide. And make sure that the wooden cow has a secret compartment that could fit a naked person. Daedalus did his job. The queen climbed into the compartment sans toga, and the cow was wheeled over to the bull. This time, the bull took the bait and mated with the wooden cow, perhaps figuring that if someone went to that much trouble, it was the least he could do.

The bull impregnated the queen, and she gave birth to a monster: a creature with the head of a bull and the body of a man. The Minotaur.

Horrified by his wife’s bastard child, the king ordered Daedalus to build a maze. And in this maze, the king imprisoned the Minotaur, where it grew into a fearsome beast that, every year or so, ate 14 virgins captured in Athens. (Not addressed in the myth: Why an herbivorous bull would require human flesh to survive.) This bloody ritual continued until the hero Theseus slew the Minotaur and escaped the maze with the help of a ball of yarn.

The tale has an interesting maze-related coda: Daedalus later ran afoul of the king and was imprisoned in his own maze. But clever Daedalus and his son Icarus escaped by making wings of wax and feathers and flying away. That’s some impressive, out-of-the-box puzzle solving by Daedalus (despite the well-known mixed results of that flight).

So there you have it: cannibalism, bestiality, and high-end carpentry. Not the storyline taught to my kids during their sixth grade Greek Festival, where they recited myths in togas made of bedsheets.

Despite centuries of digging, archaeologists have not found the ruins of King Minos’s original labyrinth. Likely, it didn’t exist in the form described by the legend. The closest parallel is the ruins of a palace from the Minoan civilization on Crete. The palace’s many connecting rooms might have inspired the myth.

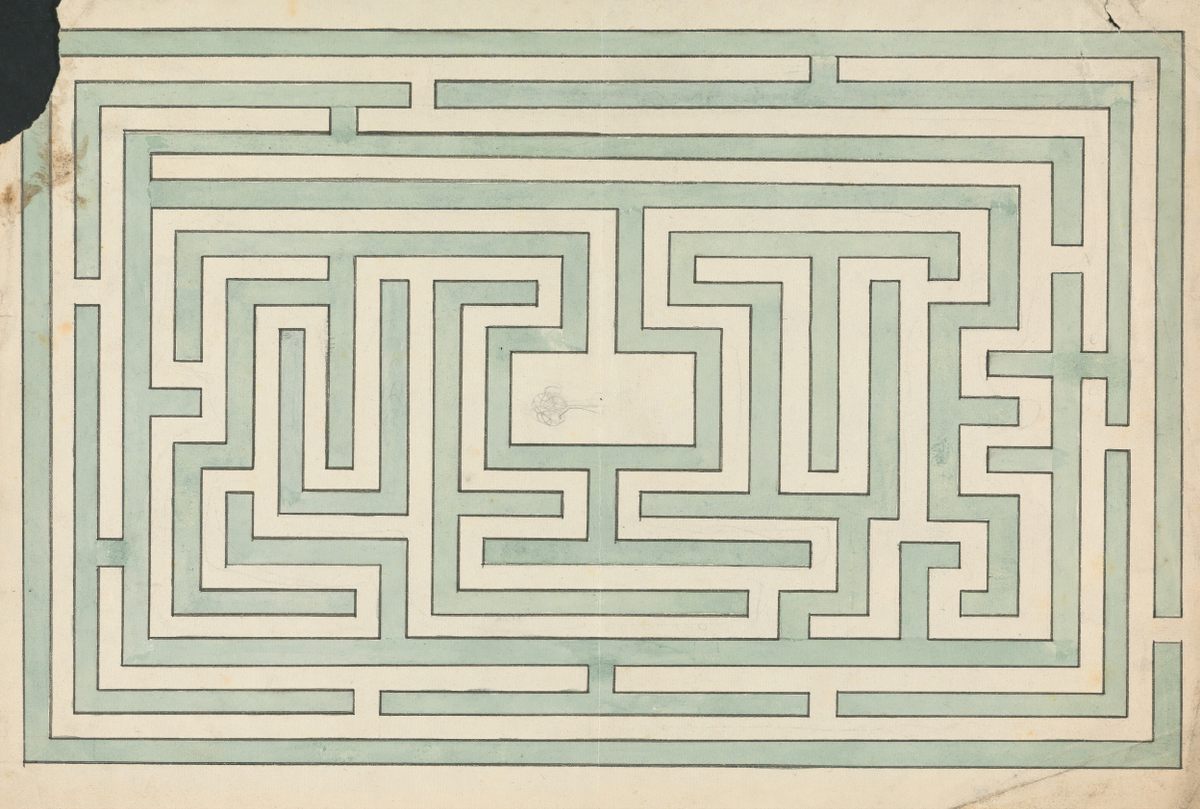

After the mazes of Greek myth, the most famous mazes are probably the great hedge mazes of Europe. Starting in the Middle Ages, it became fashionable for nobles to construct giant leafy puzzles on their palace grounds. Some still survive, including the Hampton Court Maze built circa 1700.

The Hampton Court Maze has six-foot-tall hedges made of yew. It’s a pretty simple maze, just five turns, but still, a questionable legend says that a man once got lost in it overnight and froze to death. What is certain is that the Hampton Court Maze has made an impressive contribution to science. It inspired 19th-century psychologist Edmund Sanford to put rats in mazes.

The Hampton Court Maze attracts thousands of tourists a year, in part because most mazes of yore no longer exist. Some were chopped down during the rule of Puritan Oliver Cromwell, who detested them as trivial pursuits. Others just languished.

Perhaps the most popular type of maze nowadays is made of a different plant: corn stalks.

The corn maze is of surprisingly recent origin. In the early 1990s, a former Disney producer was flying over corn fields in the Midwest when he had an epiphany. Let’s turn these boring farms into something fun. Agri-tainment!

He hired Adrian Fisher (of course) to design the first corn maze, which opened in 1993 in Pennsylvania. And here we get an unexpected cameo from Stephen Sondheim. Turns out, the Disney producer was friendly with Sondheim, and the legendary lyricist told him, “You have to call it the Amazing Maize Maze.” Which he did.

Maize mazes are now an established autumnal ritual. Late every summer, hundreds of corn fields in America get converted, a boon to struggling farmers and puzzle fans alike.

The Hardest Maze

A few months later, I did an Internet search for “Hardest Maze in America.” There’s no governing body that officially ranks mazes by level of difficulty, but one result seems intriguing: the Great Vermont Corn Maze. As one article puts it, “It’s not the Mediocre Vermont Corn Maze.”

I phone the number on the website and speak to the owner, Mike Boudreau.

“I’d love to come up,” I say.

“That’d be great,” Mike says.

“I’m thinking of bringing my son to do it with me,” I say. “How old is your son?” Mike asks.

“Thirteen.”

Mike pauses. I sense some concern.

“It’s just that 90 percent of teenagers hate the maze. They give up after an hour or so. It’s too hard for them.”

I like what I’m hearing. This maze sounds nice and frustrating.

Mike explains that it usually takes at least three hours to finish the maze, sometimes as much as five or six. “Most people find themselves back at the start after two hours.”

This is getting better and better.

Mike says he’s had plenty of customers burst into tears out of frustration. He’s seen dozens of bickering couples. “Let me put it this way. It’s NOT recommended for a first date.” One father got so exasperated, he abandoned his family in the maze, went to the parking lot, and drove off without them.

Crying? Screaming? Splintered families? I’m sold! It’s like Mark Healy’s warning came true.

“Hopefully I’ll make you hate me as much as everyone else does,” Mike says.

On a late summer day, I rent a car and drive up to rural Vermont. As recommended, my teenage son is not with me. I meet Mike, who is wearing mirrored sunglasses and a khaki jacket. He walks me to the start of the maze, a clearing with an eight-foot statue of a relatively demure Minotaur. (The monster is shirtless but is wearing a pair of blue jeans.)

I ask Mike how he got started. He says he married a farmer’s daughter, and, in 1999, in a quest to help get new income for the family farm, he set up a relatively simple maze and opened it to the public. Every year since then the maze has grown bigger and more elaborate. This year it’s approximately 24 acres. Over the years, Mike has added tunnels, bridges, statues, a platform with a motorboat. And themes! One year had a dinosaur theme, with a T-Rex carved into the rows of the maze that was only visible from a bird’s-eye view.

The year I visit—2020—the theme is more sentimental: a big thank you note to the essential workers who kept us alive during Covid. If you look at it from above, you can see the words “Thank you,” along with the symbol for medical workers, the Staff of Hermes surrounded by twisting snakes.

Because of the pandemic, Mike’s maze is allowing in fewer than half as many solvers as normal.

“I’m going f-ing broke, but I thought I’d do something to thank people.”

Another couple comes to the entrance. They’ve been here before and don’t need to hear Mike’s intro spiel. They set out on the journey.

“See you tomorrow!” Mike says.

Mike tells me that Covid is just one of the challenges of maintaining his maze. He reels off a list of problems he faces every year:

- Cheaters who use video drones to try to hack the maze.

- Hungry bears. “They’ll come at night and eat up two whole squares. They just keep eating till they throw up.”

- Climate change has made them sprout more quickly.

- Women who wear high heels. Not only is it painful for the wearer, but they leave little holes throughout the maze. Hiking boots are recommended.

- Petty thieves who steal ears of corn. “The thing is, this is feed corn,” says Mike. This type of corn is meant for pigs, not humans. “I’ve been told it’s a laxative. So when I see people walking out with their pockets stuffed with corn, I’m like, ‘You got me! You got one over on me, buddy!’”

Mike is old school. He designs the mazes himself by hand. He and his family plot the paths out with a tape measure and clear the rows with hoes and a rototiller.

“This is not a McMaze,” he tells me. Some corn mazes are made using prefab computer programs that are like giant stencils. Instead, Mike sees himself as an artisan, akin to a Brooklyn pickle maker.

It’s time for me to set out on this homemade wonder. There are three paths at the entrance, marked “eeney,” “meeney,” and “miney.” I choose meeney. I enter, and I walk between the corn stalks towering over my head. I try to use the clouds to orient myself as I make a left, then a right, then a right.

Navigating the maze is a surprisingly emotional experience. Over the next four hours, I cycle through the following feelings:

Optimism. Frustration. Extreme frustration.

Resentment—I feel manipulated, like a lab rat.

Bitterness—when I get to a dead end, I laugh out loud.

Joy—I’m making progress!

Discomfort—I’m thirsty, and my shoulders are sore from my backpack.

Smugness—I pass a dad carrying his kid in a BabyBjörn. At least I don’t have a 20-pound whining weight pulling me down.

Guilt—I inadvertently cheat by taking one of the emergency exits. Yes, this maze has emergency exits. Mike guides me back to where I made the wrong turn.

There is a science to solving a maze. Mathematicians have developed several algorithms, and before my trip, I’d printed out a list from the internet.

I’d planned to start with the easiest tactic: the Wall Follower algorithm. So named because you put your right hand on the wall, and make every right turn you can. The solver may double back a few times, but eventually you’ll reach the exit.

Or not. The maze designer can mess with the Wall Follower strategy by creating islands in the maze unattached to walls. Which Mike has done. Don’t even bother with that trick, he tells me.

I try another couple of mathematical strategies, including Trémaux’s algorithm: If you walk a passage, mark it with an X at the start and end, then avoid all passages with two Xs (I arrange twigs on the ground to make the Xs).

But if I’m being honest, my most reliable strategy is the Random Mouse algorithm. As Wikipedia describes it: “This is a trivial method that can be implemented by a very unintelligent robot or perhaps a mouse. It is simply to proceed following the current passage until a junction is reached, and then to make a random decision about the next direction to follow. Although such a method would always eventually find the right solution, this algorithm can be extremely slow.”

It is indeed slow. Four hours and 22 minutes. And that’s with an embarrassing number of hints from Mike, whom I called on my cell.

I finally finish. I reach a clearing with a red bell labeled “Bell of Success.” I kick it until it clangs. And then I get the real reward: the use of the Porta Potty of Relief (not its actual name).

Before I drive home, I reenter the maze and say goodbye to Mike. He’s standing on a wooden bridge, and I climb the stairs to join him.

“I kind of feel like a god up here, controlling people’s fates.”

He tries to be a compassionate god, smiling and bantering and giving copious hints. Less like Poseidon, more like George Burns in Oh God! Book II.

I ask Mike what life lessons he’s learned from 20 years of observing mortals.

“A lot,” he says. “I feel like I’ve gotten a PhD in sociology.”

First, the folly of inflexible thinking. “Some people learn from their mistakes. Other people—especially young men—you just watch them and are like ‘Why do you keep returning to that wall? You can’t go through the wall!’ They just won’t let go of it because they think they are right.”

Second, the dangers of trying to take the shortcuts.

“When people hear the bell, they’re like lemmings. They all just start heading toward the sound of the bell. But you’ll never find the exit just by going in the direction of the exit.”

The easy straight path is rarely the correct one. This is a circuitous maze.

A few years ago, Mike tried to emphasize this lesson by adding a second bell in the middle of the maze—the Bell of Frustration. He hoped this would dissuade people from just following the clangs.

The point is, don’t always be looking for a shortcut. Realize that sometimes, as with solving a Rubik’s Cube, you have to retreat further away from your goal before you get on the correct path.

I say goodbye to Mike and drive home. As suggested by my GPS app, I take an appropriately circuitous route of obscure back streets to get onto the George Washington Bridge.

In the days that follow, I give some more thought to the idea that mazes are metaphors for life. It’s an old theme. There’s a famous (at least to mazers) 1747 poem by an anonymous British writer:

What is this mighty labyrinth—the earth, But a wild maze the moment of our birth?

… Crooked and vague each step of life we tread, Unseen the danger, we escape the dread!

But with delight we through the labyrinth range, Confused we turn, and view each artful change.

The poem goes on until a few lines later the Maze of Life inevitably ends:

Grim death unbinds the napkin from our eyes

… And Death will shew us Life was but a jest.

So you die and the big reveal is: life was all a big joke! Even for a secular skeptic like me, that’s a little bleak. I hope life isn’t just a cruel cosmic joke. I hope it’s not an elaborate bait-and-switch prank, like when parents tell their kids that Christmas is canceled and then post YouTube videos of them crying. If life is a joke, I hope it’s a gentle and goofy joke, like a Steven Wright one-liner. (For example, “All those who believe in psychokinesis raise my hand.”)

But regardless of what lies at the end, the poem gives us some solid advice for the present: Delight as we range through life’s corridors, embrace the confusion and the inevitability of change. Enjoy that arrow between the question mark and the exclamation point.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook