For Sale: Old Photos of Huge Trees

These giants fascinated both conservationists and loggers.

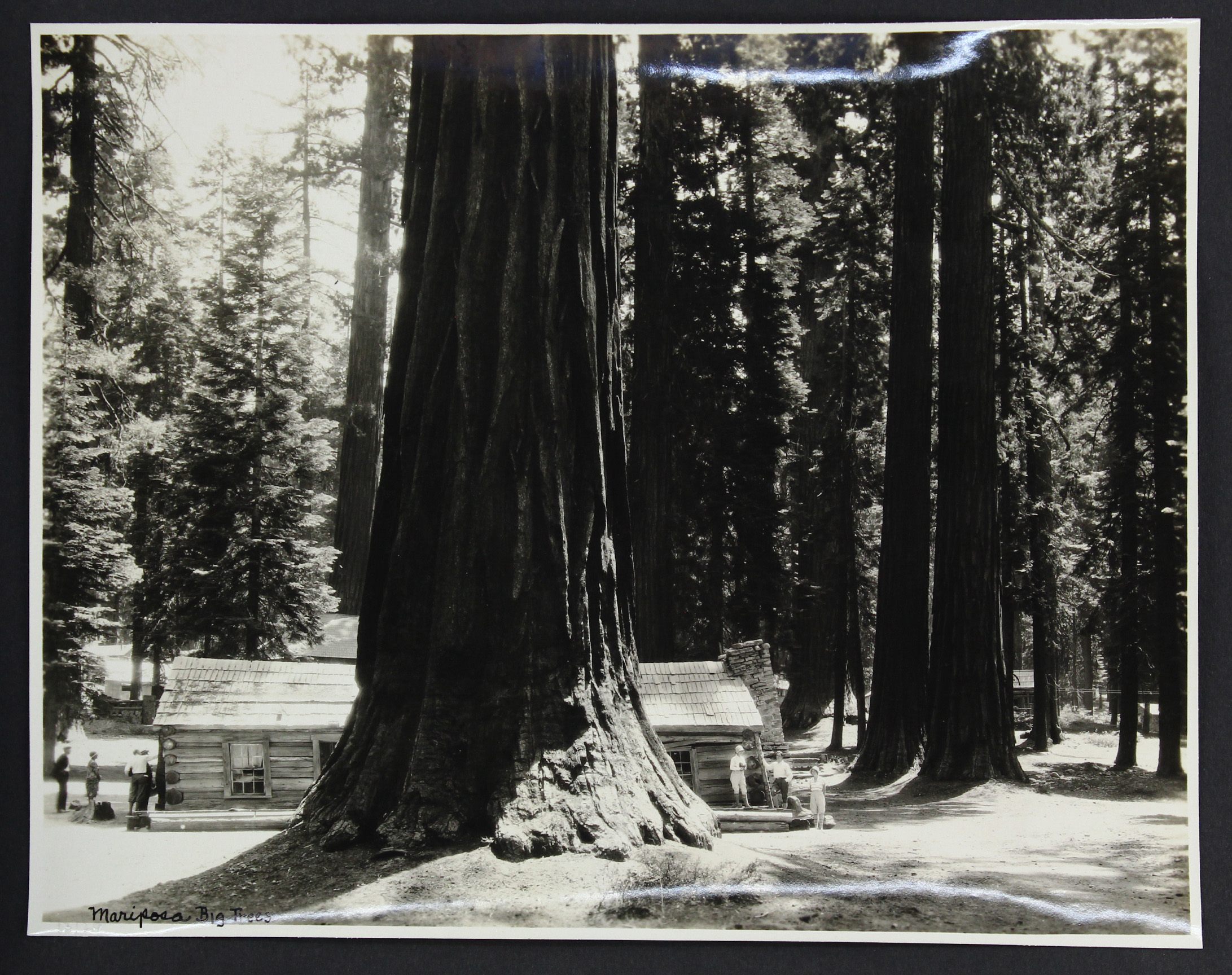

Galen Clark loved big trees whose trunks dwarfed log cabins, let alone men. Born in present-day Quebec in 1814, he eventually moved west to California in an effort to either stave off sickness or die with one hell of a view. There, he grew enamored with his soaring, leafy neighbors. In a grove that would come to be called Mariposa—in the striking swath of land that would eventually become Yosemite National Park—he found peace, poetry, and a cause célèbre: protecting the several hundred sequoias that clustered there.

An album of snapshots, up for sale this month at Swann Auction Galleries, evokes the decades when naturalists and lumber companies looked at the same landscapes with vastly different perspectives. Clark, for his part, was so moved by the state’s stately giants that he put his feelings into verse in the prologue to his volume, The Big Trees of California, writing:

“I’ve been to the groves of Sequoia Big Trees,

Where beauty and grandeur combine,

Grand Temples of Nature for worship and ease,

Enchanting, inspiring, sublime!”

Many of these trees were so hulking that burly men could seem to vanish next to their bark; some of them had grown over more than 2,000 years. After President Abraham Lincoln transferred the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove to the State of California, in 1864, and declared that “the premises shall be held for public use, resort, and recreation” for all time, Clark was appointed as its guardian. (After he died, in 1910, he would be buried nearby, watched over by sequoia seedlings he had grown from the giants in the Mariposa Grove and planted himself.)

As Clark swooned over the sequoias’ beauty, others looked at enormous trees and saw dollar signs. Even after Yosemite National Park and Sequoia National Park were established, in 1890, the naturalist John Muir—who ardently campaigned for conservation—lamented that other giants were at risk, poised to be toppled, lugged away, and turned into lumber. “As timber, the redwood is too good to live,” he wrote in The Atlantic in 1897. “God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, and avalanches,” Muir noted. “But he cannot save them from fools.”

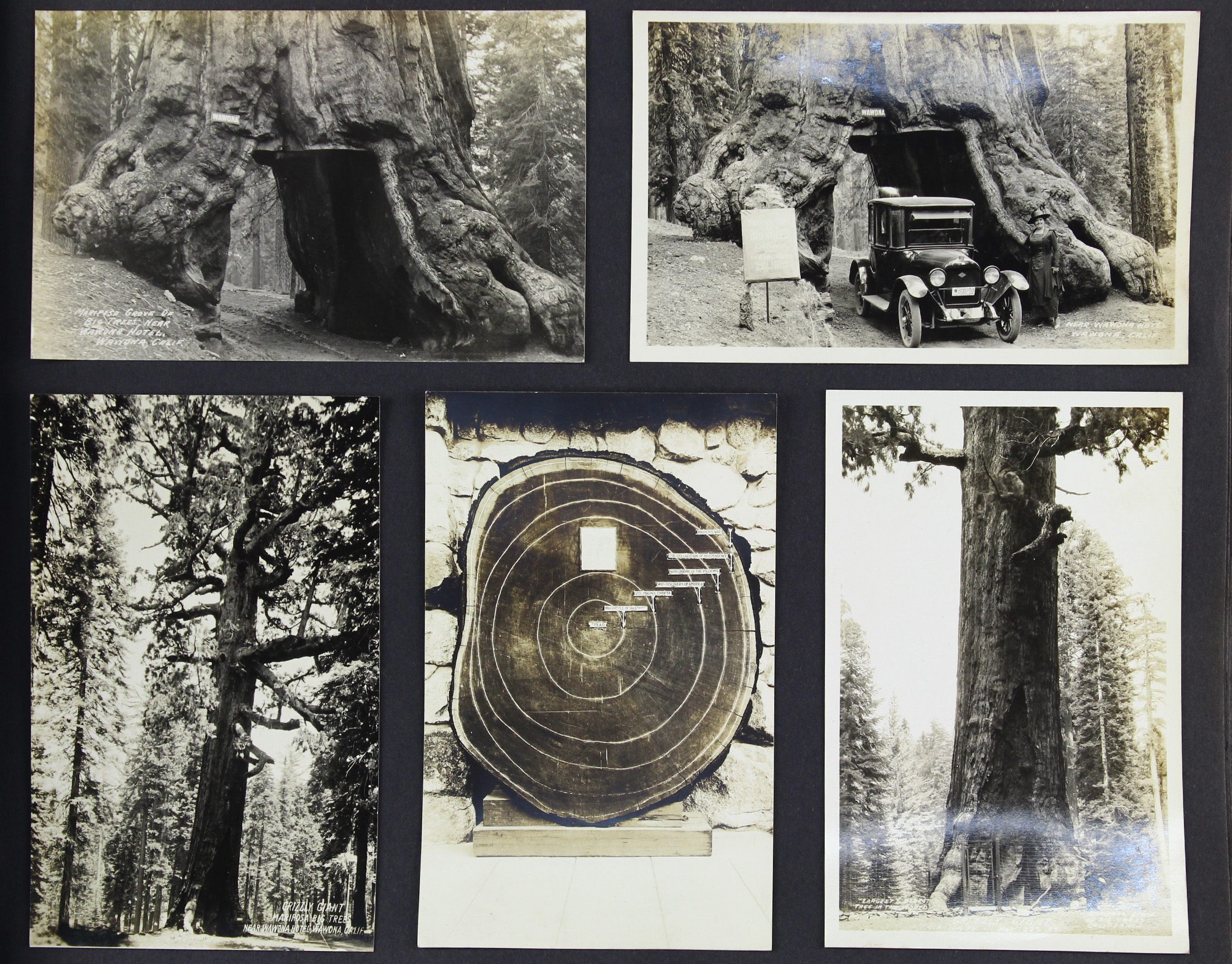

The 289 images in the album, taken somewhere between 1918 and the 1930s, survey massive trees, felled trunks, iconic vistas of Yosemite, and more. Some of the smaller-format prints may have been snatched up by tourists to bring home as souvenirs, while the larger images could have been made by commercial outfits in conjunction with the lumber companies, according to the auction house.

What the images all share is an eye toward illustrating the mind-boggling size of the trees, and the length of their lives. In some, cars pass easily through a tunnel carved out of a trunk. One image shows Clark’s onetime cabin in the Mariposa Grove, looking squat and shrimpy in the shadow of the enormous trees. Another shows a lumberjack posing against a felled giant. (Arms stretched wide, the man’s wingspan doesn’t even come close to touching both sides of the slab.) A few images seem to mingle awe and destruction. There’s one where a giant tree’s rings are annotated with the events that took place during its alleged lifespan—suggesting that this giant had seen a lot, from the drafting of the Magna Carta to the arrival of the Pilgrims. Whether the trees were living or leveled, they were wonders to behold—and to capture on film.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook