How a West African Woman Became the ‘Pastry Queen’ of Colonial Rhode Island

Duchess Quamino was the embodiment of creative survival.

In the seaside city of Newport, Rhode Island, the corner where Farewell and Warner streets cross is sacred ground. Here, inside the city’s oldest public cemetery, is the area known as God’s Little Acre, the country’s oldest and largest collection of burial markers of both free and enslaved Africans.

During the summer months, when tourists flock to the seaport, lush green blades of grass surround the markers. And when cold winds replace the blustery summer breeze, the stones defiantly jut out from the snow. About 200 markers stand in this small area, memorializing the enslaved Africans who lived and worked in colonial Rhode Island, back when Newport was a major transatlantic slave port. Most were artisans—from stone carvers and candlestick makers to chocolate grinders and bakers.

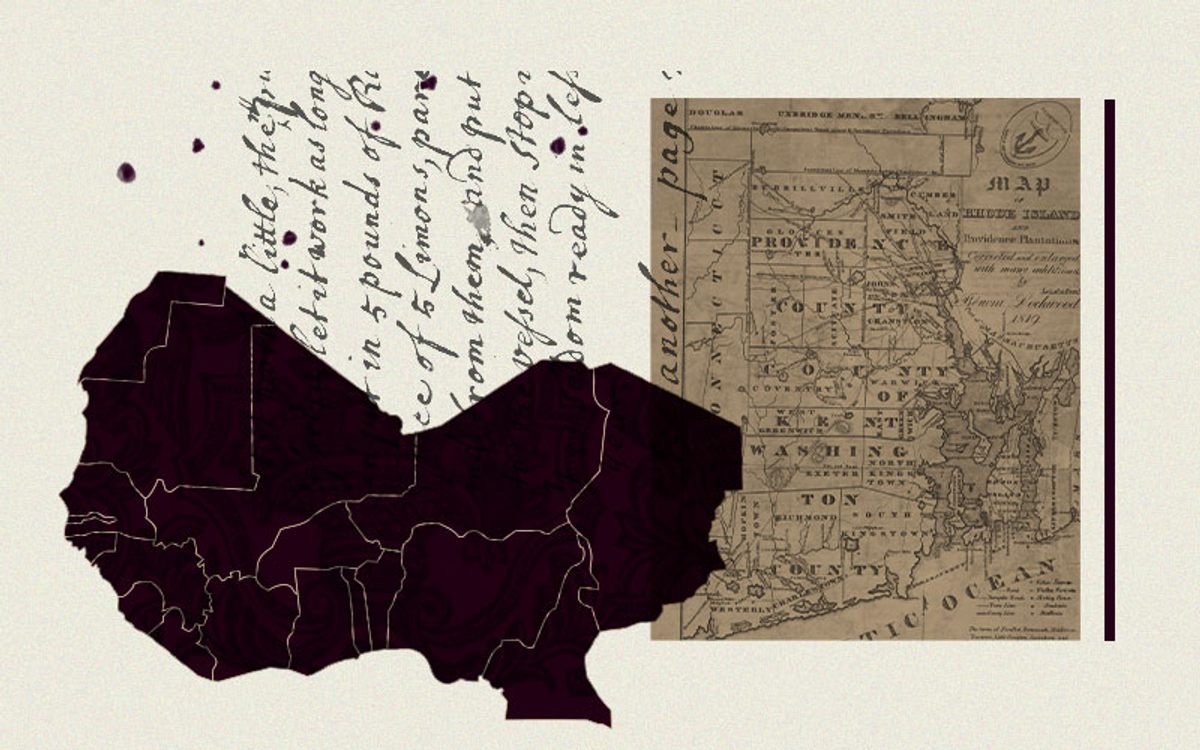

Duchess “Charity” Quamino, the “Pastry Queen of Rhode Island,” is one of the artisans found here in her final resting place. She is thought to be from either the West African countries of Senegal or Ghana, depending on who you ask. Keith Stokes, vice president of the Newport history organization 1696 Heritage Group, says that Ghana’s Gold Coast is a likely candidate for her birthplace, where she would have been born around 1753. Stokes came to that conclusion “based upon most other African arrivals to colonial Newport at that time.”

“That lines up with her husband, that lines up with dozens and dozens of other documented Africans at the time,” he says. “And as we look at the [slave] ship logs, it’s the Gold Coast that far surpasses any other West African destination.”

As detailed on her marker, Quamino died on June 29, 1804. She was 65 years old. Made of fragile slate, her gravestone has crumbled and deteriorated over the years. The legacy of her life, however, endures.

Quamino, who went by her nickname Charity, was a gifted baker. This was a skill she honed and developed while she was enslaved in colonial Rhode Island by the local Channing family. William Channing was the attorney general of Rhode Island, and his son, William Ellery Channing, would become a well-known and respected Unitarian preacher. While Quamino cooked meals for them, she started and grew her own catering business. She became, like countless other enslaved Africans who had access to kitchens, an entrepreneur.

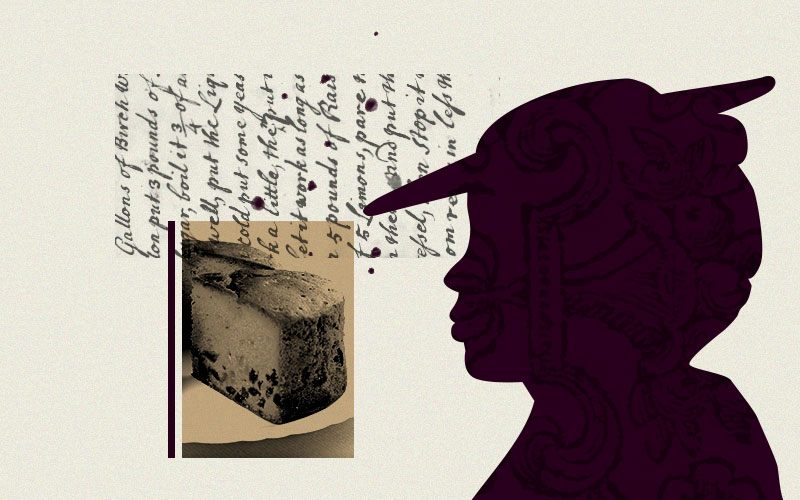

Her specialty was a frosted plum cake, which she made for the wealthy and the influential people who passed through Newport—George Washington being one of them. “There is secondary information [stating] that when George Washington arrived at Newport, she provided catering for that venue,” Stokes says.

By 1780, Quamino was a free woman. Legend has it that with money she made from her catering business, she was able to purchase her freedom. Multiple accounts mention this in the same breath as her title as the local ‘pastry queen’ and various details of her life. While this is often offered as an undisputed fact, there’s no concrete evidence that this was the case. Some accounts also state that later, she also bought the freedom of her children, who she had with her husband John Quamino.

Her marriage to John Quamino was notable, as was her piety, which is even mentioned on her grave marker. The couple were members of the Protestant Church in Newport. Between the 1730s and 40s, even as the transatlantic slave trade peaked in Newport and New England overall, the Great Awakening changed everything.

This shift represented Christian values going beyond church attendance, instead becoming embedded in everyday life and action. Both John and Duchess Quamino were swept up in the movement. “By the time she’s a young adult, even as an enslaved person and later as a free person, she’s a very pious member of the congregational church,” Stokes says. “That is a part of her identity.”

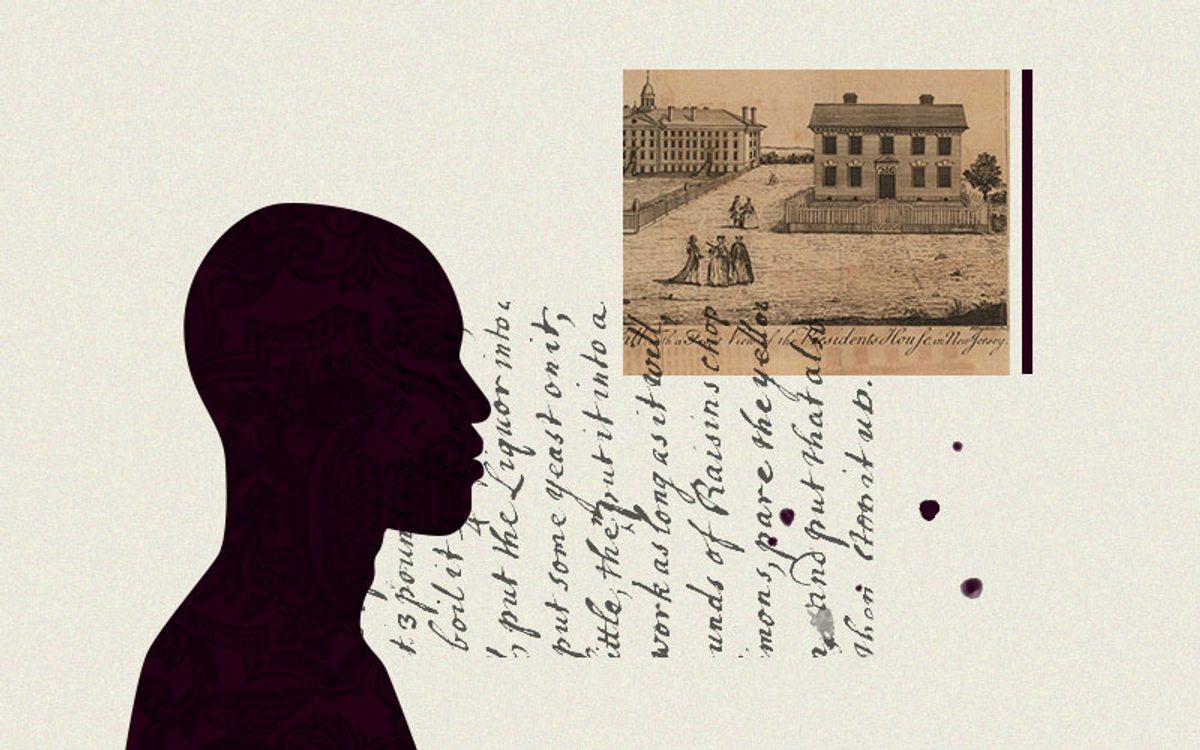

It was part of John’s identity as well. After John won a lottery and bought his freedom in 1773, his pastor fundraised to send him to the College of New Jersey, now known as Princeton, for missionary training. This made John Quamino one of the first Africans to attend an American college. He later died as a privateer during the American Revolution, a path that he had embarked on to raise the money to buy the freedom of his wife and children.

His death left Quamino to raise their children alone. But she sojourned on, making a way out of no way. Industrious and talented, Stokes refers to her spirit with a particular term. “We call it ‘creative survival,’” Stokes said. “It’s not something that the white community gave the Africans. It is something that they embraced to survive and persevere.”

Though Quamino is an exemplary example of creative survival, she is one of many free or enslaved Africans throughout Rhode Island at that time who figuratively, and sometimes literally, cooked their way to freedom. There’s Cuffy Cockroach, who is said to have developed the ubiquitous sea turtle stew of Newport in the 1760s, a soup still served in restaurants in Rhode Island today. His cooking skills were also born from enslavement. He cooked, served, and lived in the home of Jahleel Brenton, a British admiral born in Newport. Cockroach is remembered as the first caterer in the city, and each year for the winter solstice, the Brenton family hosted a dinner on Goat Island featuring his legendary sea turtle stew.

Elleanor Eldridge, who lived in Warwick during the early 1800s, was yet another one of these Rhode Island culinary entrepreneurs. Her speciality was cheesemaking. When Eldridge got in her groove, she made anywhere from 4,000 to 5,000 pounds of cheese each year. Thomas G. Williams, another caterer, also lived in Newport during the mid-19th century. He operated multiple businesses and restaurants in the city. Williams was also an activist, working alongside Frederick Douglas on the abolition of slavery, and later, Black equality.

Duchess Quamino’s story continues to resonate today. Along with her prominence in the community as both a businesswoman and a highly respected widow, she is always counted among Newport’s famous early Black cooks. A local reenactor has even portrayed Quamino at living history events, plum cake and all.

But the longest-standing tribute to Quamino is her gravestone, which was restored in 2017. The preservation of the gravestones of colonial New England’s skilled Black artisans is ongoing at God’s Little Acre. Last year, the Preservation Society of Newport received a $50,000 grant to aid directly in repairing and preserving the markers of Quamino and her fellow craftsmen in God’s Little Acre. Here, in their final resting place, their legacies are remembered.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook