Norway Will Finally Return Thousands of Artifacts to Easter Island

Sculptures, weapons, and human skulls will soon go back to the South Pacific.

In 1955, the Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl voyaged to Rapa Nui, the ancestral name of Easter Island, and collected many things: tiny carved sculptures, a stone axe, even human skulls. Though Heyerdahl promised to return the items to Rapa Nui as soon as he had analyzed them and published his findings, his death in 2002 stranded the artifacts in Oslo’s Kon-Tiki Museum, over 8,800 miles away from their home.

Now, 17 years after Heyerdahl’s death, the Norwegian government has finally agreed to return the objects to the indigenous Rapa Nui people, the first inhabitants of Easter Island, a Chilean island in the South Pacific. Last week, Norway’s King Harald V and Queen Sonja signed an agreement with representatives from the Chilean ministry of culture, marking the beginning of what will likely be a long process of repatriation.

The agreement specifies that the artifacts must be returned to a “well-equipped museum,” according to the ministry’s press release. Heyerdahl’s son, Thor Heyerdahl Jr., also attended the signing and told Smithsonian that the human remains would be prioritized in the repatriation process. The Kon-Tiki museum will retain most of its other artifacts, including the original Kon-Tiki raft as well as maps and exploratory materials the explorer used to navigate in his overseas expeditions.

The Kon-Tiki Museum derives its name from a seemingly impossible 1947 journey that made the hunky and intrepid Heyerdahl an international sensation. Heyerdahl and a crew of five crossed the Pacific Ocean from Peru to Polynesia on a makeshift raft crafted from balsa wood, bamboo, and rope—all technology available to pre-Columbian America—in order to prove the explorer’s hypothesis that ancient South Americans could have settled Polynesia using similar voyaging methods. The crew survived the journey, eating flying fish that heaved themselves onboard as well as the occasional shark. Heyerdahl’s theory was ultimately disproved by DNA research indicating that the first settlers Polynesia originated from Southeast Asia.

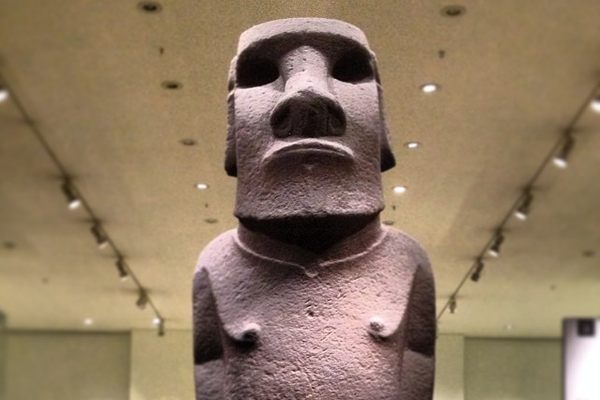

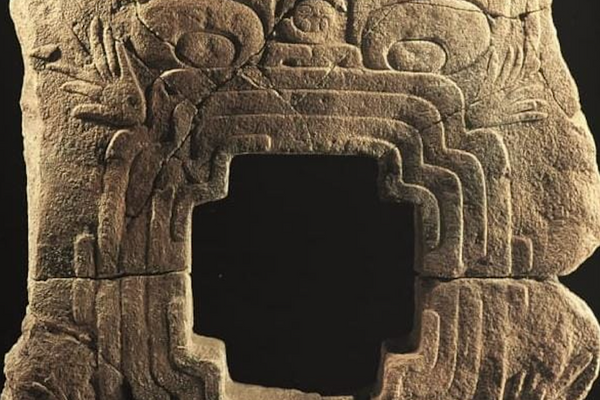

In his two voyages to Easter Island, Heyerdahl complicated several myths about the enormous stone sculptures known as moai, according to the Kon-Tiki Museum. For the indigenous Rapa Nui, moai represent the faces of specific ancestors. Though many believed the moai at Rapa Nui’s Rano Raraku quarry only depicted gigantic heads, Heyerdahl’s team excavated the statues and discovered each head sat upon an even more gigantic torso. In his second voyage, Heyerdahl attempted to solve the age-old quandary of how such enormous sculptures could have been moved to their final locations. He and 16 local residents tied ropes around the 15-ton head and dragged it a short distance by twisting the rope back and forth, resulting in a moai that moved in a shuffling kind of “walk.”

The Kon-Tiki agreement marks the first positive resolution of several of Chile’s ongoing repatriation battles. In August 2018, the Chilean government worked with the Rapa Nui people to petition the British Museum to return the seven-foot-tall Moai called Hoa Hakananai’a, or “the stolen or hidden friend.” Hoa Hakananai’a was removed without permission from the island in 1868 by the British Royal Navy as a present for Queen Victoria, who went on to donate the sculpture to the museum. “We want the museum to understand that the moai are our family, not just rocks,” Anakena Manutomatoma, a member of the Rapa Nui delegation pushing for Hoa Hakananai’a’s repatriation, told The Guardian. “For us [the statue] is a brother; but for them it is a souvenir or an attraction.”

In November 2018, representatives from the Chilean government met with officials at the museum to discuss the possibility of loaning the statue (a full return does not seem to be on the bargaining table). One possible proposal floated by the Rapa Nui delegation would replace the original statue in the museum with a duplicate, carved by the indigenous sculptor Benedicto Tuki, according to Artnet. While no concrete resolutions emerged from the meeting, museum authorities accepted an invitation to travel to Rapa Nui for follow-up talks in the coming months.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook